Hilinski Family Strives To Turn Tragedy Into Change In College Football

DawgSports

The University of Georgia’s football program is one of 123 college teams participating in the first annual College Football Mental Health week in partnership with Hilinski’s Hope.

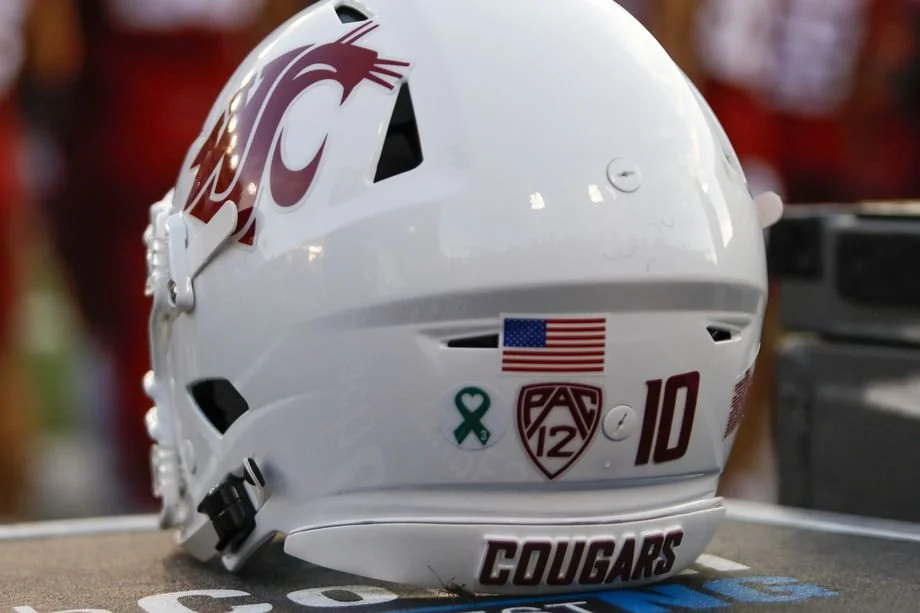

The organization was founded as a suicide awareness and prevention organization by Kym and Mark Hilinksi, whose son, Tyler, died via suicide in 2018 as a student athlete at Washington State.

I lost my oldest friend, with whom I grew up playing sports, via suicide when we were 21. I had attempted suicide a few weeks prior to his passing. His words ”give me a hug for being alive” after I told him I tried to end my own life are tattooed on my right bicep. Since then, I have had two additional failed suicide attempts. I have followed Hilinski’s Hope since the organization’s launch in 2018.

Such is to say: this cause is very near and dear to my heart.

I had the privilege of exchanging questions and answers with the family this week in order to bring even more awareness to a problem that affects many.

The Hilinski family was kind enough to provide very detailed and thorough responses to the questions I posed:

Shearman: In my opinion, it takes a lot of courage in a hyper-masculine sport like football to admit you’re having a hard time and need support. How do we support athletes who need time to step away to take care of themselves first?

Hilinski Family: Sadly, you are right; it does take a lot of courage and strength to reach out for help for mental health issues. Our athletes are very strong. Just look at their daily lives. Up early for practice, meetings, film, and lifts, then to class for most of the day, and oftentimes back to the athletic facility for more film and meetings in the evening. It takes strength and commitment to do that, to grind through long days and games. Sometimes, they don’t realize how strong they truly are. If they could just take that same approach to jump the currently high and misplaced hurdle of asking for mental health support and admit they are struggling, we would find ourselves with fewer suicides and much happier and productive athletes. Also, see answer for question number 6.

And so, how can we as a society help them do that? We feel that the single most important part of this healing process is normalizing the conversation around mental health. We need to get to a place where these athletes don’t have to be unique in that way. At H3H, we view our role to simply clear the path between the one suffering and the people that can help them. One simple way we try to do that in talking about suicide is by changing the phrase “committed suicide” to “died from” suicide. When is any other illness “committed” by a young HS or Collegiate athlete? They don’t commit cancer and they don’t commit ALS, but rather, some die from the disease process. We aren’t talking about terminally ill patients and their right to die here, we are talking about some of our most vulnerable young people.

Being kind, accepting and non-judgmental is also extremely important. We always defer to the physical injury analogy. We wouldn’t make fun of or ridicule a player for breaking their leg, tearing a hamstring, or suffering some type of physical injury or illness. We owe that same respect and care to an athlete who may need to walk away from or take time away from their sport as part of their treatment for mental health struggles.

Shearman: Why do you think players are afraid to talk about a problem that plagues many? Why do you think the stigma is especially potent in college sports and college football specifically?

Hilinski Family: The stigma attached to mental illness and mental health struggles is so very strong among athletes, particularly male athletes and football players. That stigma shouldn’t be there. That’s why we work so hard to eradicate the stigma so our uber-masculine athletes won’t feel embarrassed or ashamed to ask for help.

You wouldn’t fear going to an orthopedist if you, unfortunately, tore your ACL, needed Tommy John surgery, or going to an oncologist if you have cancer. However, you may clearly worry about the diagnosis and treatment plans-you just aren’t likely to be embarrassed about talking about it or finding the best specialist to treat you. Taking care of your mental health has to be on par with taking care of your physical health.

We also share that, just like physical injury and/or illness, the treatment and recovery process may take athletes out of the cycle of competition in their sport for an extended period of time. Each individual treatment plan and the recovery period is unique to that player. We often link the ability to continue to compete when in pain or completely fatigued to “toughness and strength,” as many of us can relate to what that must be like to “play through pain in the moment.” This is still an admirable trait or quality. Our student athletes must grind for their sport and work beyond what is comfortable. However, just like it’s not advisable to play injured or sick, it is even less so when your mental health has deteriorated to the point of suicidal ideation or constant thoughts of harming oneself. To try to deal with this alone is not advisable nor admirable. The risk is too great. Playing with a broken finger taped to the next and finishing a big game for yourself and your team is not the same level of risk. At all. Full stop.

Many male athletes learned from a very young age to “rub dirt” on their injury, even if it’s one you can’t visibly see. Thankfully, we are noticing a shift in that type of thinking. We’ve learned from the mental health professionals and sports psychologists that we work with that athletes will be much better players, much happier people (on and off the court or field) if they are taking care of their mental health, it’s all connected; mind, body and soul.

Shearman: What do you think coaches, from head coach to coordinator to position coach and graduate assistant, could or should be doing to ensure their players are taking their mental health into account before they are feeling an obligation to play through non-physical pain?

Hilinski Family: We hear from many student-athletes that if their coaches don’t buy in and truly believe that taking care of a player’s mental health is a necessity, then they won’t be likely to share their struggles for fear of losing their job on the field, losing playing time, or becoming a team outcast. As we’ve traveled the country and met with many Head coaches and their staff, we’ve learned that that fear is in the minority. More and more coaches understand and know how vital taking care of your mental health is. Beyond recognizing the importance of mental health support, coaches must fit mental health care into the schedule. They can do this by following the pillars of mental health as described by Dr Brian Hainline and team at the NCAA. This means bringing sports psychologists on staff, normalizing mental health conversations and realizing the importance of their role in this part of their athletes’ lives as well.

Having coaches and staff present during our Tyler Talks goes a long way; it says I believe in mental health and support yours. A few years ago, we gave a Tyler Talk with a top-rated football program that was attended by the head coach. During the middle of our TT one of the athletes broke down, we stopped our talk and all the athletes and the head coach went over to the player, to hug him, love him, and show their support. It was a powerful and beautiful moment. one that could have gone very differently. But it didn’t. We’ll never forget that moment.

Shearman: What other resources can you direct people toward if they experience these world-ending thoughts?

Hilinksi Family: As you know, we aren’t mental health professionals, but we have teamed up with some incredibly amazing people in the space. Through their experience and research, we’ve developed Hilinski’s Hope Game Plan and our H3H online mental health lessons to guide and reinforce the importance of mental health education and care. These, however, aren’t tools to help an athlete in immediate crisis. If someone is struggling and needs urgent support, they need to call the national crisis hotline number 800-273-8255 or text the new three-digit 988 suicide crisis hotline number. Our Hilinski’s Hope bands have the crisis hotline number on the inside of each band. We’ve heard from many athletes that when they were in a very dark place, they turned our H3H bands of hope on their wrist inside out, and called the crisis hotline number, and got the critical help they needed. We see schools moving toward more and better-qualified resources for student athlete mental healthcare. We support these onsite professionals as loudly as possible to remind our SA’s that there is help right now on campus. Take advantage of these precious resources. There are also many companies with the resources and programming to help schools meet these needs immediately while building or growing their own. Not having mental health resources available is becoming more concerning as we get more student athletes to ask for help. Not having those when they are needed most is not acceptable.

Our goal from the very beginning was to change and save at least one life. We hope we are doing that.

Shearman: What words of encouragement would you have for someone too afraid to open up about these sorts of thoughts that affect not only their own life, but that of those around them?

Hilinski Family: When we meet with student-athletes across the country, we always tell them that it’s a strength, not a weakness, to reach out and ask for help. But that can be very difficult for athletes to believe and act upon. They do have to grind and be strong as they play their sport, but there is a difference between grinding through a game and practice and trying to grind through mental health struggles.

In our Tyler Talks, we let our athletes know that if they can’t take that first step and ask for help if they can’t start that conversation, we encourage them to use Tyler’s story, share it with their family, friends, coaches and/or teammates, and then let that trusted adult know how they are doing.

We hear from many student-athletes after our TTs, by email or text, some also call, to let us know that’s what they did. They started a conversation about their mental health struggles by starting to talk about Ty’s tragic story and are now getting the help they need.

Shearman: What do you see in terms of the first step of institutional change in taking care of student athletes’ mental health?

Hilinski Family: The biggest institutional change a school can make is to prioritize [mental health]. To do this, the Administrations will need to properly budget and fund this portion of the student athlete experience. We see many stories about schools hiring multiple FTE’s to assist their teams with NIL questions, processes and opportunities. Do the same and even better with mental health. Nothing says support as loudly as writing checks to make the gravely important work of mental health care for their student athletes a priority. Sharing their successes in this regard at conference meetings and national speaking opportunities further facilitates the adoption of best practices for the benefit of all our players. Be financially explicit, act with the urgency this topic demands, and take the job of caring for all their student athletes seriously as they do filling seats and make the playoffs. Engage alumni, be loud and lead. Let this be a part of your legacy if you are in a position of leadership on campus.

Shearman: With how quickly you’ve expanded your Tyler Talks and podcast presence, does the organization plan on having athletes share their stories so you all can potentially host multiple discussions in different locations on a given day?

Hilinski Family: Such a great question! We didn’t anticipate Hilinski’s Hope growing so quickly. We started out as a grass-roots effort in Washington and South Carolina and it’s now national, which is truly humbling and something we are very grateful for, ONLY because it means that more athletes are listening and taking care of their mental health. We think the mission of H3H has spread and cultivated because there is such a need for mental health care and support among athletes. So many athletes see themselves in Tyler, someone who was at the top of their game, loved by their teammates, family, friends and coaches, but they aren’t happy and they can’t place why, and they’re afraid to ask for the help they need.

This growth needs funding as well. We will always be indebted to the countless donations over these past 4.5 years, and we have turned those dollars into the best action we can. But as we continue, we will need to find true financial partners that can help fund this growth and meet the ever-rising increase in demand. We remain in awe of those who do this to turn good ideas into good works. Those contributions and partnerships will save someone you might least expect. Tyler might have asked for help in this newer environment-it’s the thought we wake up with and go to bed with each night; drives us to continue our mission. How can we save the next Tyler?

We’ve had and continue to have many student-athletes on our Unit3d: Conversations for Student-Athletes podcast to share their stories. It’s really hard to listen to because we hear Tyler’s voice in their words, their journeys are very powerful and we know they are helpful to their fellow athletes who are listening in. There’s a certain respect others have for their own. Hearing a student athlete talk about their struggles helps those in need realize that they are not alone.

We’ve partnered with other similarly aligned mental health foundations to have such stories shared on a grand scale; “Strength in Stories” comes to mind. We met virtually with athletes across the country, with chat room breakout sessions and focused topics.

Hundreds of athletes joined and were able to listen, exchange dialogue, and find support in a group of strangers who live parallel athletic lives; the grind, the stress, the anxiety, the fear of underperforming and fear of letting their team, coaches and fans down were all discussed. Throw in what COVID did to their collegiate careers, NIL deals, social media and unkind fans; our student-athletes have so much they deal with, and they need to talk about it. Doing so with people/athletes who understand and share similar stories is powerful and extremely helpful.

We’d love to get back to that space and give these athletes a place to share, be heard and understood. Thank you for reminding us of this question!

I’d again like to thank the Hillinski family for their brutal honesty and in-depth responses on such a delicate topic. You can find their organization and donate at www.hilinskishope.org/

Most things are bigger than sports. Be kind to each other. Take care of yourself.